The daring genesis of Las Meninas

Miguel Usandizaga

usandi.cadop@gmail.com

Text and drawings by the author.

Translated by DeepL

Presentation

The one we reproduce below is an exceptional, unique text. And if we say so emphatically, it is not because we are suffering from an attack of vanity. Not at all. We are simply stating objective facts. Because, let's see, when has it ever happened that a successful author calls someone to write (attention: and sign!) the last chapter of the book he is about to publish? Huh?

We can't think of any similar situation, and it goes without saying that we are very proud that it happened to us. Because we haven't - contrary to what the misguided might think - paid a single euro to get it.We must remember that in these absurd times in which we live, paying to be published is common, at least in the academic world, which is governed by the imbecilic slogan of "publish or perish", an extreme overvaluation of research productivity that makes the expression "they are publishing like crazy" be used as praise.... It doesn't matter "what," but only "how much" is published. The more the better. Whatever it is, it doesn't matter.

The best result of this publication mania that plagues the university, turning it into a buffoonish fight to the death to improve the number of Hirsch and the ranking position of everyone is, of course, the Ig Nobel prizes.And the saddest thing is to see that nowadays only the most pitiful sectarians and charlatans are successfully pursuing a university career. Naturally, with the due and very honorable exceptions.

Well, in this panorama we have the honor to say: no, we only publish if a friend asks us to do so. The nonsense of publishing for the sake of publishing, for fear of dying, or that some sinister court made up of boffins and crooks will suspend our lives, fortunately does not go with us, fortunately. Not anymore. There had to be some advantage to getting older.

Sorry, we had lost the thread in our indignation.Let's get back to the matter at hand: to round out the unusualness of the origin of the text that follows, the book that includes it as an addendum (Without figuration, little fun) is a reworking of the first book by its author, the architect, designer, painter and Writer Oscar Tusquets. That previous book, entitled Everything is debatable had sold out of editions, and had become untraceable. To remedy this situation, Oscar Tusquets decided to rework it.

The new book includes a number of excellent photographs from the web artwithOSCAR, published by Eva Blanch, taken during the couple's travels and showing Oscar looking at the places, buildings, works of art or things that the book comments on. Thus, the book ends up having three authors with different degrees of responsibility: a married couple... and a friend of theirs who writes I don't know what unintelligible things about Las Meninas. Menda, yours truly.

Oscar Tusquets proposed us to participate in the book by completing chapter 51, dedicated to Las Meninas. We were delighted to accept, and he gave us the text of the book and the beginning of the last chapter, which ended with the question of Eva and Oscar's daughter, Valeria, about the mastiff wonderfully painted by Velázquez. We continued from there, trying to bring our study of Las Meninas closer to the curiosity of a child.

We now publish that chapter with some corrections that we hope will make it easier to read and with the animated illustrations that the computer support allows us. We have already warned you several times, but we must insist: if you start reading what follows, at the slightest headache, dizziness, blurred vision or any other symptom you may experience, stop reading immediately and definitively. We would not want to feel responsible for anything bad.

The book presentations were great, we had a great time: in Barcelona we were on stage and, in the audience, our admired Carles Sans, one of the members of El tricicle: el mundo al revés.... We were even able to sign books. The way we are going, at this point in life we thought we would never be able to do that, and it made us angry. So, when we saw that Eva was sitting next to Oscar, and that the world was upside down, we put it on our backs, we sat next to her and, hey presto, to sign, as if we were Antonio Gala or Almudena Grandes?

Happiness is never perfect. Oscar had warned us with his usual impudence: "you will flirt a lot". But Oscar does not know the amount of Basque blood that circulates through our veins and that totally disqualifies us for this type of activities we suppose to be pleasurable? Shortly after we were signing, a wonderful lady -a friend of Eva's- stood in front of us and put the open book on the table. Shyly, we signed. We didn't know that, in addition to signing, you have to write a dedication. The poor lady stared at the book for a moment and confessed: "I don't understand"... I: "...sign...". Eva, very kindly, took the hint: "most signatures are not understandable...". Embarrassment. Flirting? "Good! All my life living in Pamplona, and now I'm going to need you to accompany me home when I leave the ball..."

On the other hand, at the presentation of the book in Madrid, Boris Izaguirre, after hearing our explanations about Las Meninas, concluded, "How cute!" What more could you ask for? To publish just for the sake of it, without obligation, and on top of that to receive the most scientifically founded academic praise... Fuck the "sexenios de investigación", "journals indexed in the first quartile" and "punts PAR d'activitat de recerca"... This is life!

The daring genesis of Las Meninas

VALERIA:Dad, look at the dog!

OSCAR: It's the best painted dog in the history of Art. Dalí was once asked: "If the Prado Museum were to burn down and you could only save one work, which one would you choose?" and Dalí answered: "I would save the air of Las Meninas because it is the best quality air there is". Notice, Valeria, in the atmosphere, think that in the upper part of the canvas... there is only air.

VALERIA: Dad, and the dog is sleeping?

In the Prado it is forbidden to take photographs, which I think is very, very good. However, Eva, discreetly, from abroad and with her cell phone, left a record of this failed paternal lesson.

This book, which begins by stating that "without figuration there is little fun", closes with the most "fun" figurative painting in history. I mean that, besides being the best painted, it is the most complex, the most mysterious, the one that raises the most questions. I don't think there is another work that has given rise to so many analyses, to so many learned texts, to so much high-level controversy. I gave my modest opinion in the chapter "Understanding Las Meninas" in my book Pasando a limpio. The latest contribution comes from an architect, Miguel Usandizaga, full professor at the Polytechnic University of Catalonia, a friend with whom Lluís Clotet and myself have been exchanging congratulations and objections on this issue for more than a year. I find his controversial theory very convincing, I only object that the vision of the kings in the mirror -whether foreseen from the beginning or a final addition to satisfy the monarchs- is an absolutely brilliant contribution in the sense of representing something that is "outside" the painting in a position that coincides with those who are observing it: we occupy the place of the kings. I told Usandizaga that I would like to mention his theory in the conclusion of this book, that why not write a short and informative text that we could include here. As you can see, the text is rather long and relatively informative, but it is so new and interesting that we have decided to reproduce it in its entirety.

VALERIA:And the dog is sleeping?

MIGUEL: I'll explain it to you right away. The dog is not asleep. The boy in the foreground of the painting on the right, Nicolasito Pertusato, has just woken him up by kicking him and Velázquez paints him in that very short time, two, three seconds, in which the dog still resists waking up.

Las Meninas is a painting full of mysteries and curious things like the one you just reminded me of. So much so that some of its mysteries have gone surprisingly unnoticed. For example: Las Meninas is not one painting...but two.

Velázquez's workshop produced two versions of the same painting during his lifetime: The one we have all seen in the Prado

Museum (we will call it the large painting) and another much smaller one (the small painting) that is currently part of the collection of the English National Trust, which exhibits it in the mansion of Kingston Lacy, in the county of Dorset.

The vast majority of experts -and also the owners- affirm that this small painting of Las Meninas is a copy of the original by Velázquez, painted by Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo. The only dissenting voice is that of Matías Díaz Padrón, who maintains that the small painting predates the large one and that it is a "sketch or modeletto" of the large one, and that it was painted by Velázquez.

Díaz Padrón's thesis is objectionable for several reasons: he assumes that Velázquez would have copied the large painting from the small one, but why would he have painted the small one first? Didn't he know how to paint it directly in large? Díaz Padrón suggests that Velázquez painted the small one so that the king would let him paint the large one. That is even more untenable, because it supposes that the king would have approved a sketch in which neither he nor the queen appeared... because in the small painting the kings are not painted in the mirror in the background.

Having abandoned Díaz Padrón 's thesis, let us return to the other: the small painting would be a copy, by Velázquez' s son-in-law, of the large one.

Would Velázquez -and the king- have let Martínez del Mazo sell a copy of one of his paintings? To whom, why, to make a little money? All these are anachronisms, things that did not happen at that time. But the small painting.

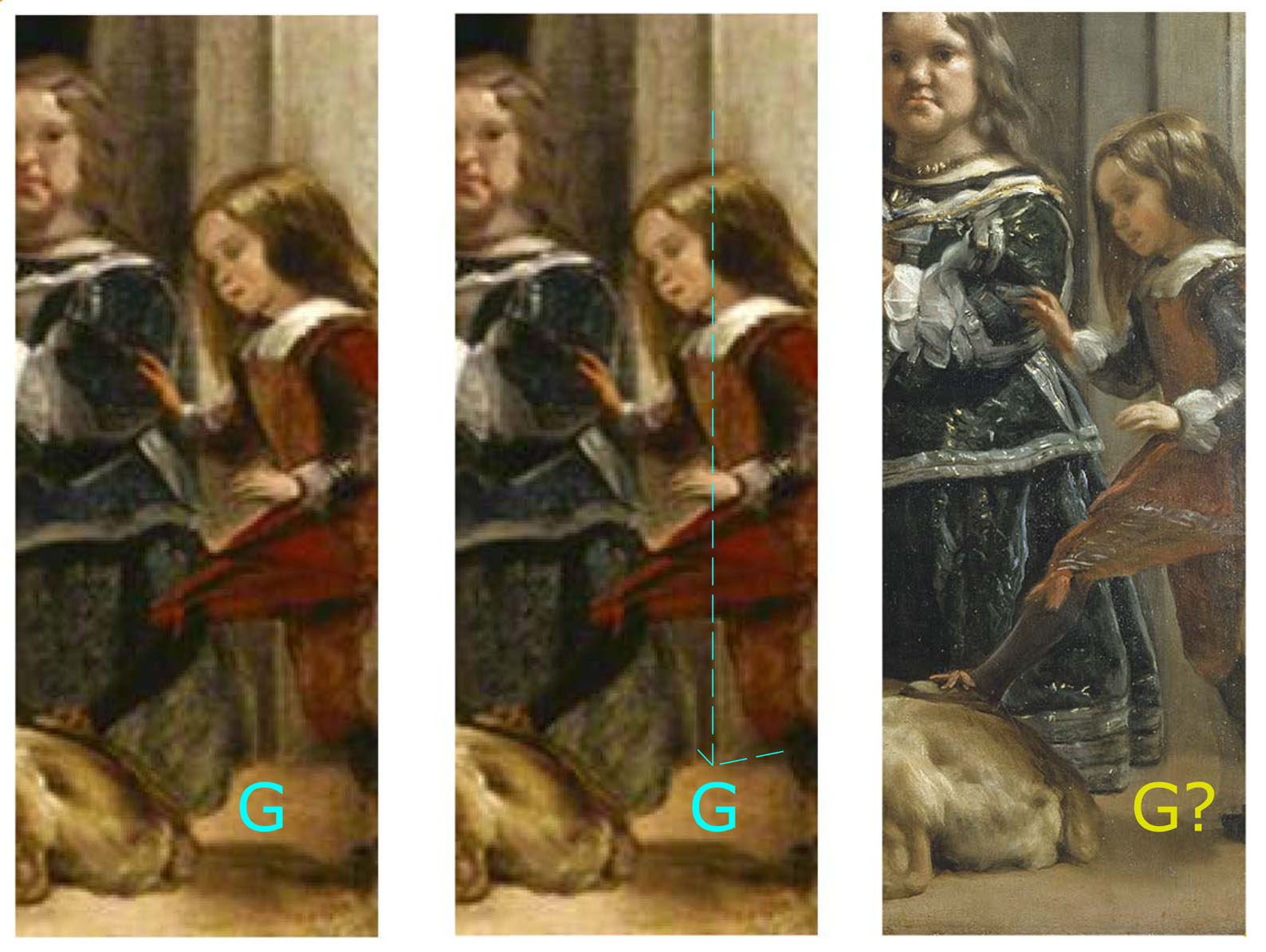

was indeed sold by Velázquez's workshop during the master's lifetime. Without the portraits of the kings, it is worth remembering. And, above all, the small painting cannot be a copy of the large one because of a detail that we discovered when we traced the two paintings as a preliminary step to analyze their perspectives, a detail visible in the small one, but not in the large one: the continuation under Nicolasito Pertusato's left leg of the vertical line "G": the corner of the window in the foreground of the painting. Eight centimeters of vertical line. Almost nothing, a trifle, a minutia... but a crucial minutia to understand how Velázquez painted Las Meninas. That line is visible in the two paintings above the head, but, between Nicolasito's legs, only in the small one. This shows that the small painting is not a copy of the large one, because a copyist cannot invent and paint something that he does not see in the original. It also seems reasonable to think that the figures of the small one are painted on a pre-existing background, which showed that full vertical line, in all its height. That background is the one that constitutes the general straight lines of the space of the painting, the perspectives, which are absolutely coincident in the two paintings, except for the difference in size (see Fig. 3).the perspective of the large one could perfectly be a photographic enlargement of that of the small one. On the other hand, the figures in one and the other paintings are quite different.

Here is the problem to be solved: if the small painting is neither a copy nor a sketch, if it was painted neither before nor after the large one, what the hell is it, when, for what purpose and by whom was it painted? The only solution we can think of for this enigma is clear, though not obvious: neither of the two paintings was painted in one go, and a part of the small painting - the perspective - was an indispensable instrument for the painting of the large one.

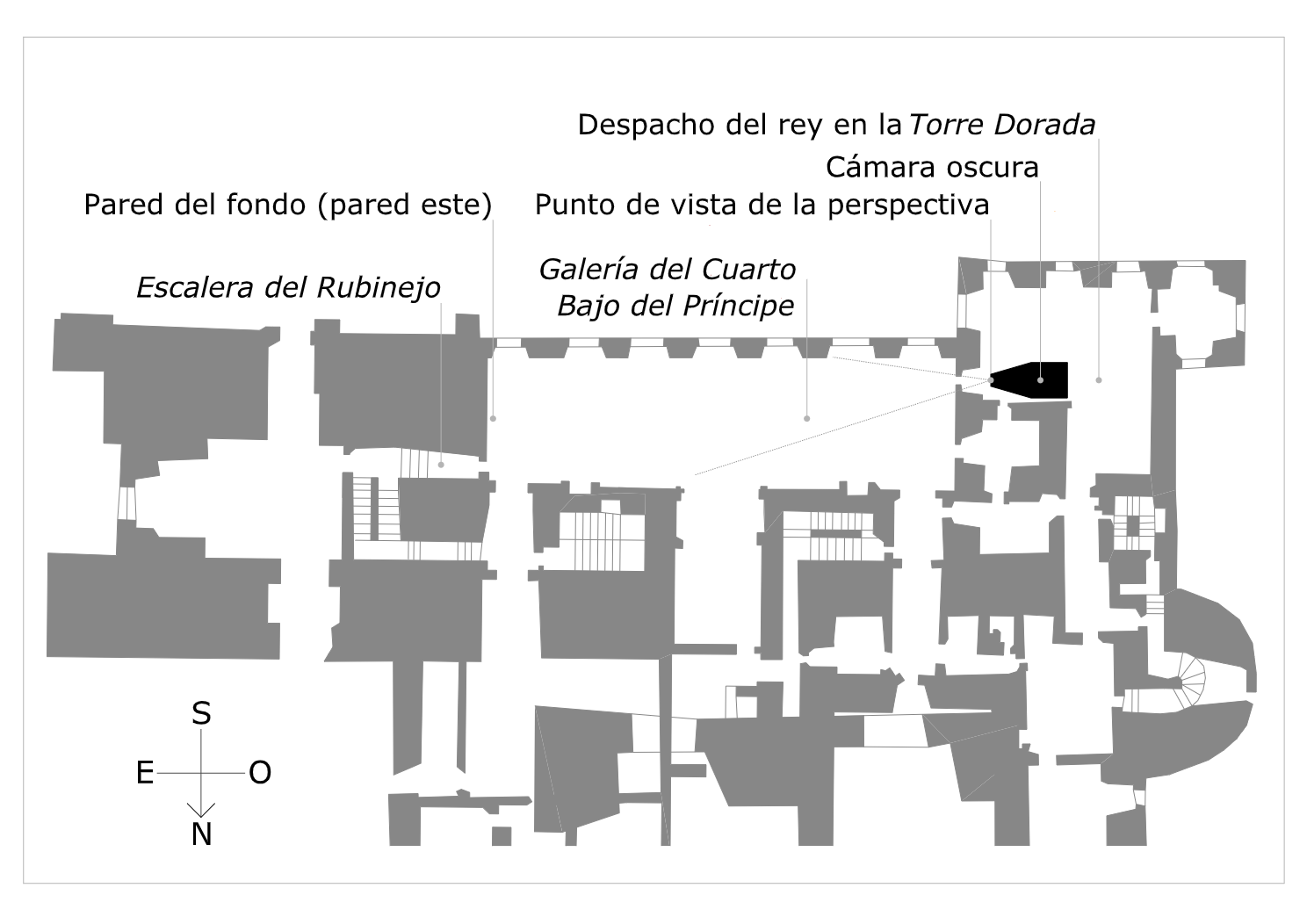

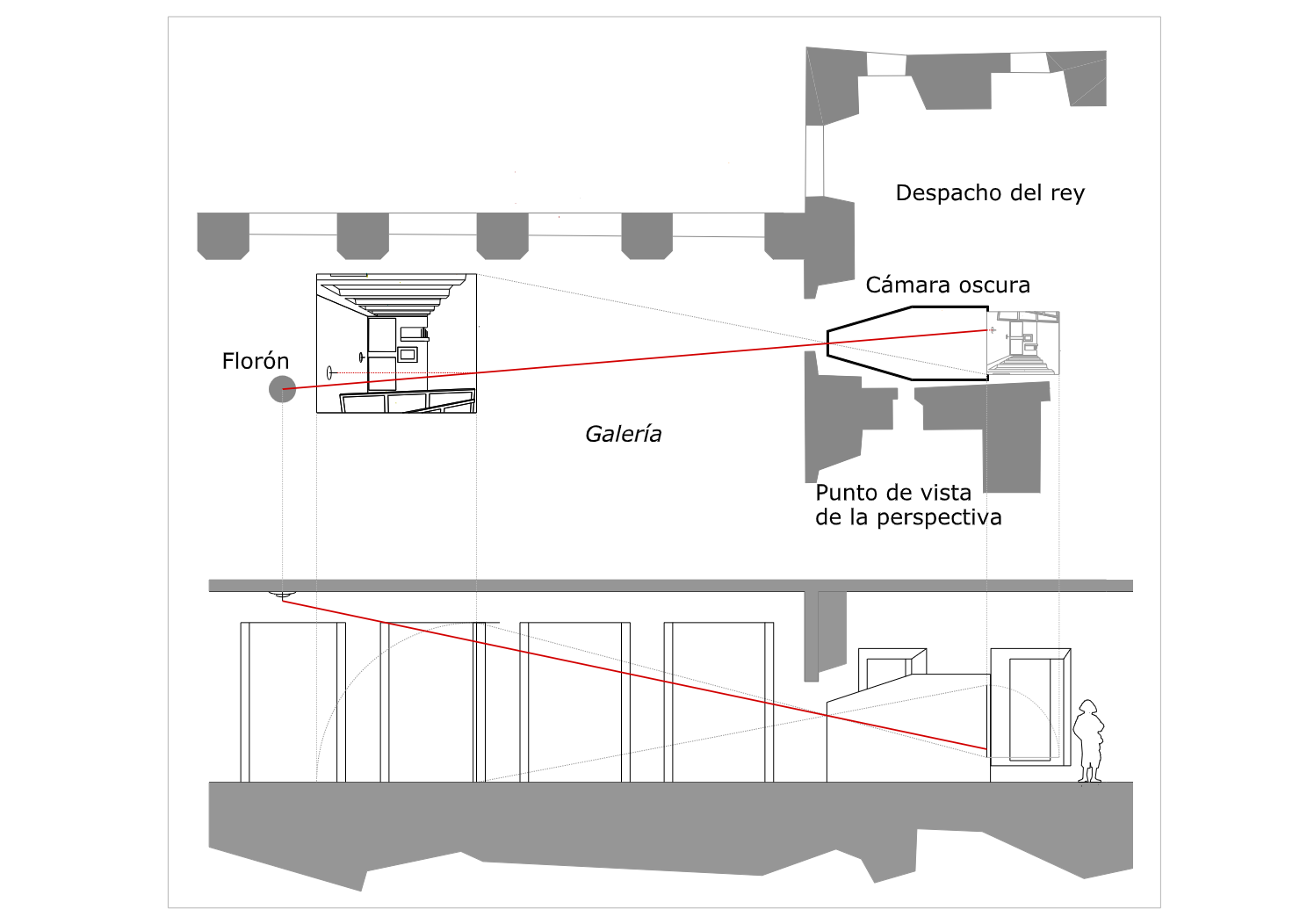

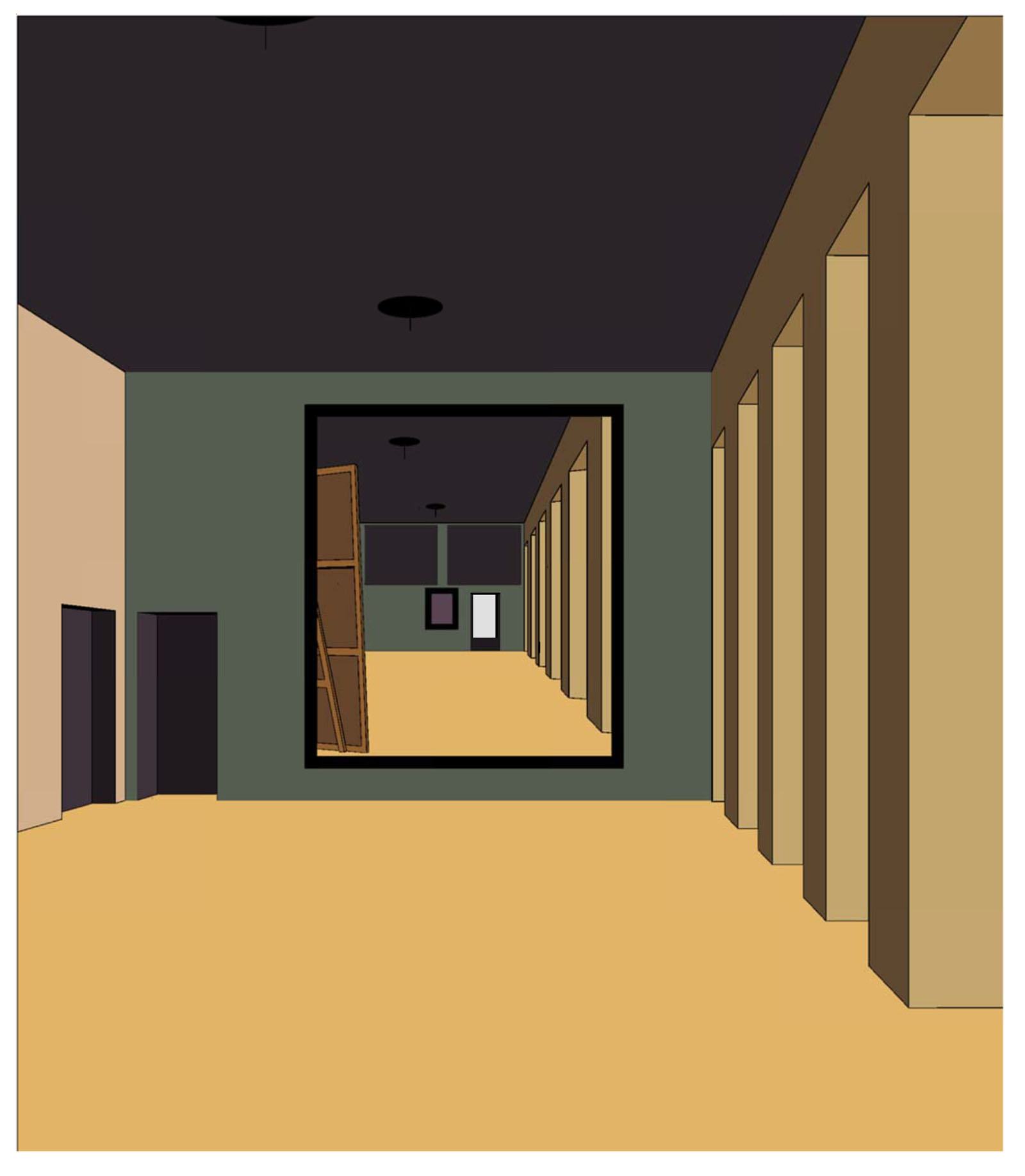

How? We know that the two pictures were painted in the same place, the Galería del Cuarto Bajo del Príncipe (hereafter "the Gallery") in the Alcázar, the palace of the kings, in Madrid. And the two paintings represent the Gallery seen from a point of view that is in what was the king's office in the so-called Golden Tower. The building was completely destroyed in a fire in 1734, but fairly accurate plans are preserved (see Img. 5).

Changing its side would have involved a demolition and reconstruction work too complex and time-consuming for the time available. Velázquez did something much easier: paint it on the other side.

Velázquez completed and painted the perspective on the small painting, and re-hung it upside down on the back wall inside the camera obscura. He was going to use it as what in photography is called a "negative".

VALERIA: What is a negative?

MIGUEL: Jo, Valeria..., you make it difficult for me. Let me explain it to you... The old photographic cameras, the ones that were not digital, the first ones took black and white photos, very small images, which appeared by means of a chemical procedure when the camera was triggered and the light (and the image, as I told you a while ago) entered on a transparent film impregnated with a substance that reacted to the light and were stored in reels that usually had 24 or 36 photos. In those reels the photos appeared with the black and white reversed. That is why they were called negatives. Then these negatives had to be developed -or positive-, which was done by projecting an intense light through them (in a small darkened room, like a camera obscura...), on papers with an impregnation similar to the one on the reels. On those papers the negatives were inverted again, and became positives. They were the copies of the photo, much larger than the negatives. Do you understand me?

VALERIA (with a resigned face): Well, not much…

By reversing the operation of the camera obscura, illuminating its interior and darkening the Gallery, that is, using the camera obscura as an opaque projector, Velázquez projected the small painting onto the blank canvas of the large one. As the small painting hung upside down, its projection was in the correct position.

1. FIGURES IN THE BIG PICTURE

Velázquez painted them from life, without the aid of any object other than, probably, a mirror.

2. FIGURES IN THE SMALL PICTURE

They were painted, by order of Velázquez, by one of his collaborators (probably Martínez del Mazo), copying them directly from the large one without using any machine. Once the figures were copied, Velázquez sold the small painting.

3. PORTRAITS OF THE KING AND QUEEN IN THE MIRROR AT THE BACK OF THE LARGE PAINTING

Velázquez painted them, probably at the request of the kings, only in the large painting, after having sold the small one, without even taking down the painting, as if they were reflected in a mirror.

Still later, someone added to the large painting the cross of Santiago on Velázquez's chest.

The mystery of the other painting of Las Meninas, the one by Kingston Lacy, is thus solved. It is neither a sketch nor a copy, it is what in the language of photography is called a negative, a "pictorial negative" of the perspective. And the large one is a print by enlarging the perspective of the small one, the negative.

I'll be done in a moment... I just want to add that Velázquez did not use the camera obscura to paint (as many people believe when they hear that Velázquez, Vermeer and many others used it), but only to accurately trace perspective.

Why such an insistence on Las Meninas, when Velázquez, in general, did not seem to be very interested in perspective? Because even before he started painting, Velázquez had decided where he wanted to hang Las Meninas: on the back wall.

Hanging there, the painting would look like a gigantic mirror that would reflect reality, inseparably linking it to its representation. We cannot prove this last hypothesis in any way, but it seems to us as baroque as it is plausible and attractive.

Nothing more. Valeria, forgive me for the long-windedness. You know that we teachers measure time in hours... Tell your father that we thank him very much for the incredible generosity with which he welcomes us in this book of his. Let's hope that it will help someone else to read and believe us...

Ilustrations

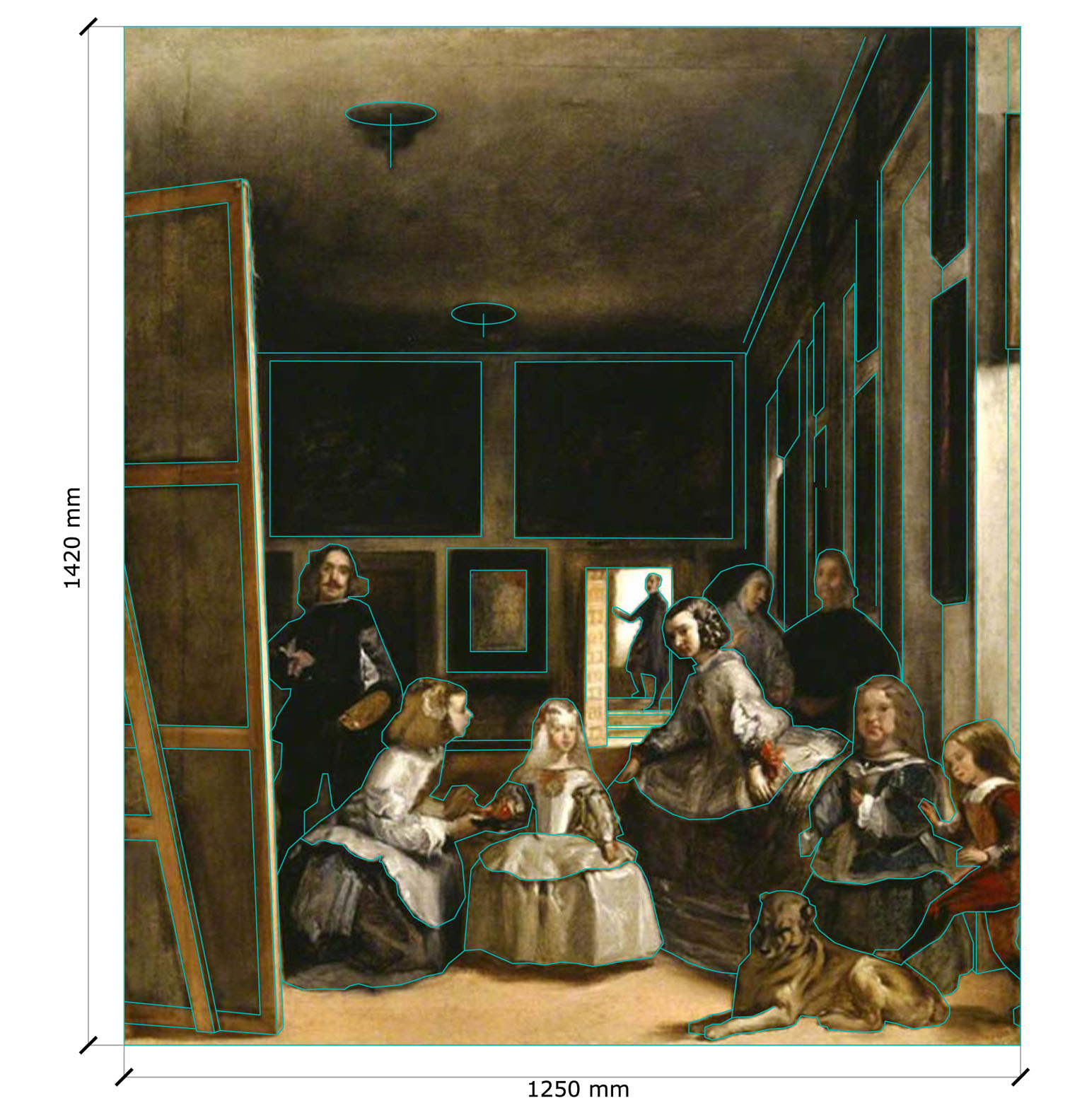

Img 1. Diego Velázquez,Las Meninas, 1656, Madrid,

Museo del Prado. (Height 318 cm. Width 276 cm.) (enlarge)

Img 2. Taller de Diego Velázquez,Las Meninas, s.d. Kingston Lacy Estate, National Trust. (Height 142 cm. Width 122 cm.) (enlarge)

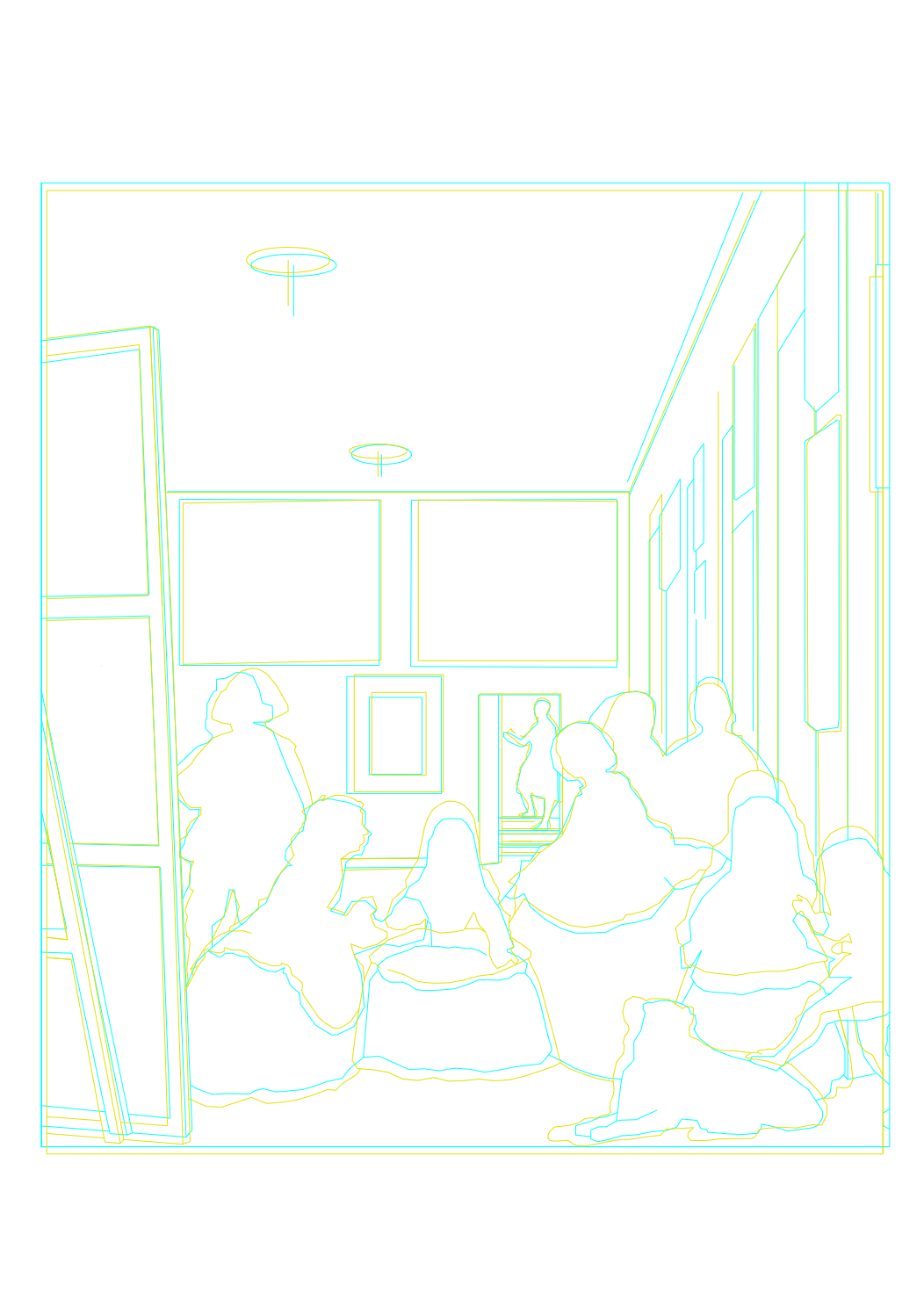

Img 3. Superposition of the perspective and figure casts of the two paintings. In black, the large Prado painting, in red, the small Kingston Lacy painting.

(enlarge)

Img 4. The L line in the two pictures. Left and center, Kingston Lacy. Right, El Prado.

(enlarge)

Img 5. Tracing of part of the plan of the first floor of the Alcázar of Madrid, according to the original plan of Juan Gómez de Mora, from 1626, in the state it was in at the time of painting

Las Meninas. (enlarge)

Img 6 (enlarge)

Img 7. Isometric view of the previous image (Img6): Velázquez painting a ceiling fleuron in the large painting of Las Meninas. The line of strokes joins, from left to right, the existing fleuron on the ceiling of the Gallery, the same painted on the large painting, the shutter of the camera obscura, and the fleuron on the small painting, hanging upside down on the back wall of the camera obscura.

Img 8 (enlarge)